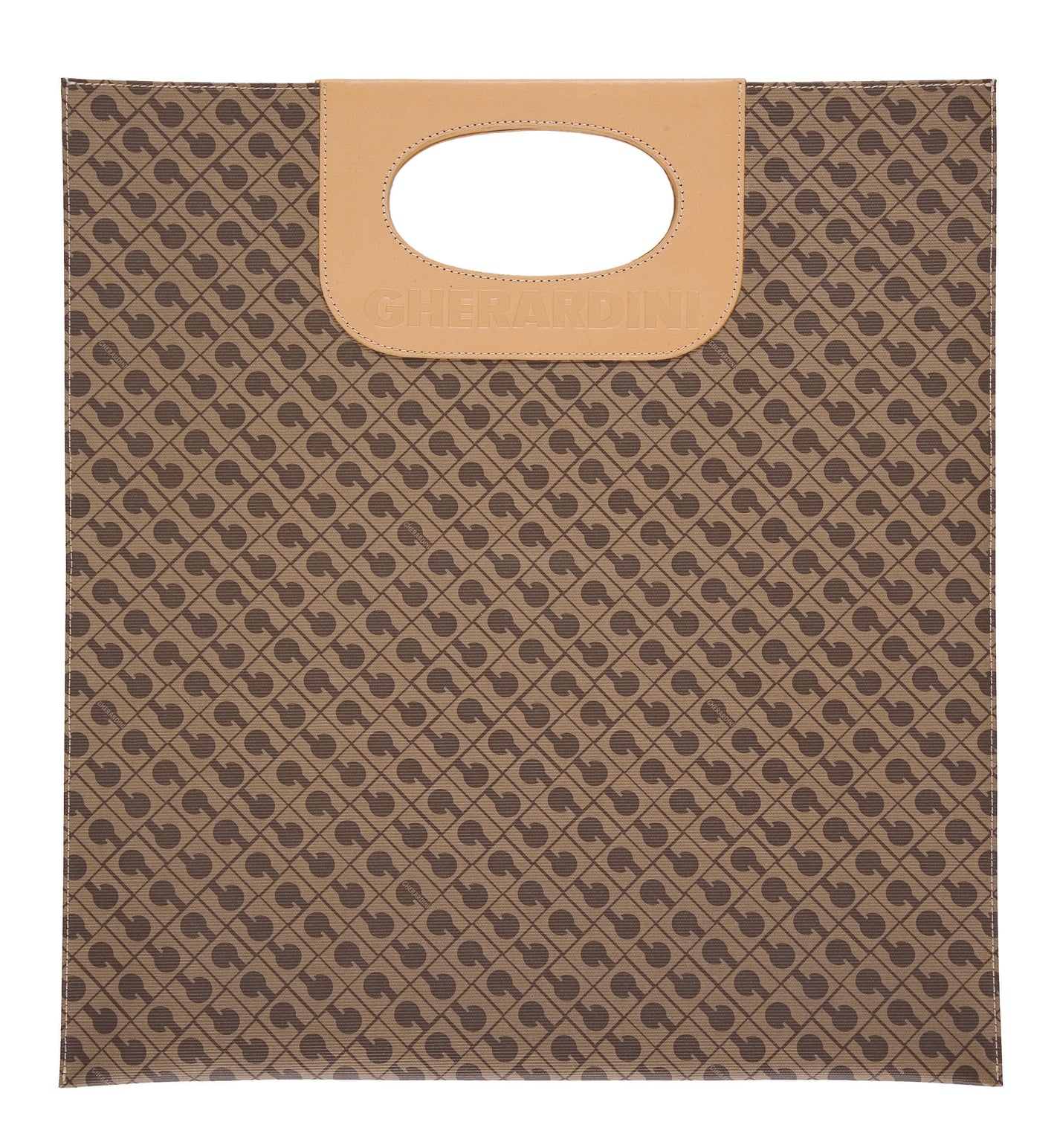

Behind the name Gherardini lies a great story, the long history of an activity that is an expression of the skill and ingenuity of Florentine handicrafts and thus an illustrious representative of the world of Made in Italy. The members of the family who managed this brand until 1990, leaving an unmistakable mark on its style and production, were able to create and regenerate themselves constantly, investigating and providing responses to the ever changing needs of their customers and adapting to them by finding, through research and experimentation, materials and techniques that gradually became better suited to the object to be made. The firm, founded in 1885 as a manufacturer of cases in Florentine leather, in fact turned to making other kinds of leather goods, in particular accessories and above all bags. In the area of the production of new materials, perhaps one of the most significant events was the use in the seventies of a new ultralight and resistant but soft fabric in the manufacture of raincoats and large bags. It is interesting to note, though it may seem obvious by now, how the trademark “G” sometimes became, as in the Softy bags themselves or in the suitcases and traveling cases, as well as in the umbrellas and raincoats with the same coating, the sole and constant element of decoration. A true icon, a great emblem of design. It is comforting to know that Gherardini's wealth of expertise has not been lost but has been taken up by the Florentine Braccialini family, which has acquired the brand and started to conduct an international operation aimed at launching new models based on such historic ones as the 1212 bag. Nor is this all. Perhaps the most important fact is that they have chosen to preserve the craft methods of production, while the market is assuming a different scale and as a result Made in Italy is spreading further in the world, even in the East.

A year ago the heir to the company, Susanna Gherardini, conscious of the brand's historical and artistic importance, decided to donate to the Galleria del Costume of Palazzo Pitti, a museum devoted to the history of fashion, a collection of models of bags and purses that mark some significant stages in the development of Gherardini's production, in terms both of the techniques of manufacture and of the distinctive character of the model, despite being accessories that we can define as “classics,” that fall into line with fashion while going beyond fashion. Susanna has also donated part of the eccentric wardrobe of her mother, Signora Maria Grazia Lunardi Gherardini, whose style constitutes an example of how it is possible to be unique and original by commissioning your clothes from experienced and refined couturiers, but guiding them with your own ideas in the elaboration and choice of models.

Catherine Chiarelli

Director of the Costume Gallery of Palazzo Pitti in Florence

Destiny was already there in his first name, Garibaldo: that of the leader of a modern “house” of fashion, a standard-bearer of beauty and elegance, a defender of craftsmanship and of those Florentine qualities that remain a bastion of style. And then a surname, Gherardini, whose origins stretch back in time and perhaps all the way to a young lady, Mona Lisa, called La Gioconda, who with that mysterious smile which Leonardo da Vinci gave her is still the most admired woman in the world. Are we going too far? Not in the least, given that the life and history of Garibaldo Gherardini are the mainstay of the beautiful but true tale that we are about to tell and that makes the Gherardini brand as it celebrates 125 years of existence a magnificent example of the adventure of Made in Italy. The first in order of seniority, but not for that reason alone.

A history that runs from the end of the 19th century, right through the 20th and into the 21st, maintaining unchanged its original values, the heart, the courage and the passion that led a young man of just twenty-four with great hopes to set up shop in the spring of 1885. Years all spent bearing that name, Garibaldo, that is itself an intrepid manifesto of the family from which he sprang, patriotic to say the least, and of the Florence that, after expelling the grand duke, experienced between 1865 and 1870 the ephemeral and perilous glories of becoming the first capital of Italy before yielding to the grandeur of Rome, without regrets and still less rancor, returned between wistfulness and disappointment and drinking as Ricasoli put it “a poisoned chalice.” It was in this city of illusions and disillusions, to which thirty thousand state officials had moved and where the Savoy court went for strolls in the Boboli Gardens, that Italy and the Italians took their first steps. It was in Florence, up to its eyes in debt as a result of the effort to accommodate the monarchy, with the municipal budget in tatters but the desire to go on being the Athens of Italy, that Garibaldo grew up (he was born on March 28, 1861, a few days after Unification). And perhaps he saw, while still a boy, the bronze copy of Michelangelo's David in the middle of the square, in the June of 1872, and then—who knows?—even the curious transport of the original by means of a special contraption from Piazza della Signoria to the Accademia, where it stood in splendor from July 30, 1873. At home, when he was thirteen, he would have heard of the arrest of the female workers from the cigar factory, of the strikes of the braiders, of the shocking rise in the price of bread, of the first arrests of internationalists who may have been on the same side as the father who had given him that not very “holy” but highly popular name, a creed and a symbol that was to accompany him throughout his life and right up to his death on June 12, 1945 (almost a year after the liberation of Florence), given that he would be buried in the atheists' cemetery because he chose to be cremated. Where he still remains, in the shade of a fine sepulchral monument that portrays him in all his vigor, with the Sunday best hat and mustaches of the upright man.

And we can imagine that young man wearing a white smock stained with wax and leather throwing open the shutters of his workshop, first on Via del Fiordaliso and immediately afterward on Via della Vigna Nuova, where the story of Gherardini began and still continues today, in those early days of 1885: a man with the desire to hit the big time nursed by every pioneer, the grit of the craftsman who knows that he is building on the work of his colleagues in the medieval guilds, the cuoiai and galigai, dressers and tanners, and the enthusiasm of every twenty-year-old seeking to make his way in the world. Amongst the cases that he sketched and roughed out with his first workers, those caskets for ladies and shaving sets for gentlemen that he covered with Florentine leather, decorated with gildings and flourishes that recall the designs of Renaissance palaces, especially the Palazzo dei Rucellai almost opposite designed by Leon Battista Alberti and then a few steps further on Palazzo Strozzi, much of it built by Benedetto da Maiano, perhaps the most beautiful stone building in the world. And for him too, just as many years later for another creative person like Emilio Pucci, it must have been enough for his work to draw inspiration from the magnificence of his city, from its colors and its details, from that genius loci which would later bring success to Guccio Gucci in 1921 and to Salvatore Ferragamo at the very beginning of the thirties when, returning from the glories of Hollywood, he acquired the ancient Palazzo Feroni Spini to serve as a home-cum-factory. But Garibaldo Gherardini was the first of the great inventors of Made in Italy—and today some would perhaps even call him a designer-entrepreneur—to understand that there were not just boxes and frames, cigarette cases and delicate minaudières. He saw that it was possible and necessary to go down another road, that of the fashion world still in its infancy and of leather goods with their multitude of accessories for men and women, for every hour of the day.

The years in which the house of Gherardini was born were a time of great change, and not just because they saw the renovation of the whole of the historic center and the destruction of much of the city's vestiges of the Middle Ages with the demolition of the ghetto, because the architect Giuseppe Poggi laid out the boulevards ringing the center and their new squares, because for seventeen years people argued over what the façade of the cathedral was going to look like, a façade that was finally unveiled on May 12, 1887. Garibaldo would have celebrated like everybody else and put his best products on display: for the king and queen were arriving on the banks of the Arno, and there were regattas, tournaments and gala performances in the Salone dei Cinquecento, inaugurations of the Horticulture Show and the Photographic Exposition and even a pageant representing the entry into Florence in 1367 of Amadeus VI of Savoy, surnamed the Green Count. A civic passion and pride equal only to that of Garibaldo Gherardini, who saw members of the new middle class, no longer made up solely of landowners, pass in front of his workshop every day, as well as those elegant processions of Anglo-Florentines who left such a mark on the city's landscape. New customers for new objects. People in love with the authentic Florentine character, filtered perhaps by the idea of an English-style Renaissance, like Princess Ghyka at Villa Gamberaia or John Temple Leader at the Castello di Vincigliata or Arthur Acton at Villa La Pietra. The Anglo-Florentines were crazy about the city, even bringing the elite sport of golf there with the Florence Golf Club dell'Ugolino, which was founded in 1889. The year before that Queen Victoria had come to the city and stayed there for over a month, her royal train greeted with great festivities. The fame of Gherardini and other outstanding Florentine craftsmen (recorded in many illustrious writings by Giovanni Spadolini) grew, as did that of its publishing houses, especially Le Monnier, its schools, such as the Istituto di Scienze Sociali Cesare Alfieri or the Scuola di Disegno Industriale which was to become the glorious Istituto d'Arte di Porta Romana, and its newspaper La Nazione, founded by Bettino Ricasoli in 1859 and the first in Italy. Carlo Lorenzini's The Adventures of Pinocchio proved a great success and in 1891 The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well also came out, filled with the frugal recipes of Pellegrino Artusi. Not to mention “spoken Florentine,” the nation's only tongue in its early days according to Manzoni's criteria. In short, Florence as capital of excellence and by ancient vocation of that high craftsmanship which is still one of its vaunts today.

Set square, bone folder, rules, punches for decorations, a pair of compasses for circular cuts, skiving knives and gigs for gilding were the work tools of Garibaldo Gherardini and his men. They were used to make cases, letter holders for writing desks bearing the family coat of arms, cigar boxes, leather picture frames and medal showcases, as well as the first balloon clutches in black moiré with clasps of openwork silver mounted by hand and embellished with semiprecious stones. This was the idea: moving from what we would call a design object today to the creation of fashion. Starting with the evening bag that revolutionized the canons of female elegance and that would then turn with the development of women's independence and emancipation into the true handbag, perhaps their staunchest ally and the holder of a thousand secrets. At this turning point too the Gherardini firm was unique, boasting a wholly Florentine résumé that immediately attracted an international clientele and elite customers. The new century, the 20th, was born, and in the early decades, between the twenties and thirties, luxury models took off: austere clutch bags or festive pocketbooks with the invention of the jewel clasp and the use of brocades, two-pile velvets, satins and pleated hides for a refined and at times flaunted luxury, with the plus of being “handmade,” and in Florence at that. In the air in the city were the exploits and languishing poses of Gabriele d'Annunzio, who from the early years of the 20th century lived at the Villa La Capponcina in Settignano, surrounded by horses, greyhounds and endless debts. Poet of female beauty and of elegance in things, he may have had a considerable influence on the style of the time.

Both the First and the Second World Wars would bring hints of measured austerity and utilitarian elegance. Garibaldo was growing old and brought his sons Gino and Ugo into the workshop, where they would assist him with respect and dedication for many years, until the final parting in 1945, when the firm's founder was eighty-four years old. His sons learned the techniques and treatments, while the world changed. First there was Fascist Italy and its autarkic fashion, then the terrible war with its disasters and fears. New ideas and new energies were needed in the workshop, now turned into a factory but still located in a few rooms on Via della Vigna Nuova, on the street front as well as on the second floor of a townhouse where at lunchtime skivers and squares were downed and the saucepan with their meal in it was brought out. Just like at home, in the Gherardini household.

The Gherardini Family

The name Gherardini derives from Poggio Gherardo, a hill near Settignano. The Gherardini arrived in Florence around a thousand years ago, moving into a small palace with a tower in Por Santa Maria, near the Ponte Vecchio. They were regarded as “a distinguished and honorable family,” loyal for better or worse to the party of the Guelfs. Thirty-eight Gherardini were awarded the Order of the Golden Spur, and representatives of the family “mounted and rode their horses immediately behind the bishop” in public processions. Sanctioned and threatened with death, Cece Gherardini became part of Florentine history in 1260 for his attempt to dissuade his companions in the Guelf party from declaring war against the Ghibellines of Siena, a war that culminated in outright disaster at Montaperti. Vicissitudes of a political nature obliged various members of the Gherardini family to seek asylum in France, England and Poland. It more seems that the noble Fitzgerald family of Ireland can trace its origins back to these lost Gherardini. The branch of the family that descends from Francesco di Girolamo was called Gherardini della Rosa because its members were awarded the Golden Rose (by Pope Martin V, lord of Montici), which became part of their coat of arms, and their palace was located on the aristocratic Via Maggio in Florence. It also seems that Mona Lisa—the young wife of the elderly Francesco del Giocondo immortalized, at the beginning of the 16th century, in Leonardo da Vinci's famous portrait—was a Gherardini. The genealogical tree of the family includes merchants, statesmen, influential members of the Wool and Merchant's Guild, mercenary leaders and even heretics. Two Gherardini, Alessandro and Tommaso, were highly thought-of painters in the 17th and 18th century. So the “prehistory” of the Gherardini, traced in the local chronicles and in legend, is an important legacy that is still held in great esteem in the development of the brand, both for marketing activities and in the style of the line of production.

In 1948 Mauro Biffoli was taken on as an apprentice at the Gherardini workshop at the age of just eleven. He learned to attach the fastenings with stitches hidden under the clasp and to make bags that stood up without a framework, but only thanks to the skill of his hands and the quality of the leather. Today there are few such accomplished craftsmen and no one is better able than he to describe the qualities of the materials used by Gherardini. After the Second World War many women of the wealthy middle class used to commission the models of their bags from the Gherardini, after buying the fabric and clasp themselves. In fact the customer often wanted the bag to be made out of the same material as her dress, or had been captivated by a length of cloth displayed in a shop window, perfect for a chic accessory. Biffoli says that the most sought-after suppliers in Florence were Lisio for fabrics and Settepassi on the Ponte Vecchio for clasps. The Gherardini often bought materials from Lisio and Settepassi to make the firm's models. In fact Lisio had excelled since 1906 in the production of fabrics in which the yarn was interwoven with gold thread. Settepassi on the other hand was already famous in the 19th century, a reputation that it had gained through the sale of the celebrated necklace of sixteen ropes of pearls that King Umberto gave to Queen Margherita.

The fabrics utilized by the Gherardini ranged from two-pile velvets to lamé brocades, from satins to pleated grograms. From Austria they imported cloth adorned with beads and precious fabrics decorated in tent stitching with floral motifs or mawkish scenes inspired by 18th-century painting. As for the jeweled clasp, many bags were embellished with gems, enamels and precious metals; sometimes even with genuine pieces of jewelry like cameos painted with profiles of women. However, the Gherardini were renowned in particular for their bags made of leather, a material selected in its finest varieties and worked in such a way as to make it lasting and resistant as well as elegant. In fact the accounts tell us that it was the Gherardini who invented the type of leather known as Florentine cuoietto, taking their inspiration from the Tuscan craftsmen of the 16th century. They were also famous for their bags made of python, lizard and crocodile skin, and Biffoli recalls that where the latter was concerned the Gherardini were the first to make use of cuts from the belly. In those years, in fact, these were discarded by other fashion houses owing to the large size of the scales, too big for bags that were generally of small dimensions. On the contrary they proved perfect for bulkier models like the Bellona.

July 1952, the modern image of our country is born. And the Made in Italy phenomenon takes off, that complex mix of talent, courage, spontaneity and enterprise that the whole world envies and tries to imitate. And the Gherardini firm, in those frenzied days of a feverish and at times grim postwar period, is ready for recovery, indeed for the new battle for international success. In the workshop on Via della Vigna Nuova the production of objects and small leather goods slowly gets back underway and they start taking orders again for bags made to measure out of the same fabric as the customer's dress, while new tools and machines are bought. The workers do the cutting and send part of the production to be sewn outside the company, by small chains of trusted artisans; at midday they stop work and take their lunch out of the saucepan, while on the street the promenade starts up again. There are even a few tourists, despite the fact that the whole of Europe is still licking its wounds from the Second World War. What today we would call the Gherardini brand is born, but with its roots still deep in craftsmanship, the roots of Garibaldo and his early workers, who have passed through two wars and now want to clamber out of the rubble and poverty.

And with them the whole of Italy. At the workshop in those days, following the death of its founder, his legacy of ideas and manual skill has been inherited by his sons Gino and Ugo, who have steered the company through some difficult years. But now, in the fifties, the world has changed. Cases and frames are no longer enough. They have to launch themselves into the open sea of fashion that, right there in Florence, is about to blossom amid the glories of the Sala Bianca. And completely hand-sewn leather bags become the stars of Gherardini's production in the hands of the cousins Pier Luigi and Roberto. Gino and Ugo's sons, they make the family “G” famous, in part with their evening bags of satin and lizard-skin, always adorned with the magnificent and precious clasps that are the house's distinctive trademark. Going for them the Gherardini grandsons had the enthusiasm of youth and that genius loci, widespread and unequalled, which in those years made Florence one of the world's most envied and admired cities. For it was here that Italian fashion was born, with the enterprise and genius of Giovan Battista Giorgini and his shows, first in the private setting of Villa Torrigiani and then under the eleven Bohemian chandeliers of Palazzo Pitti, in a Sala Bianca echoing with the voices of American buyers and reporters, who had rushed over from Paris to see the new talents of modern elegance at work: that handful of pioneers who had taken up Giorgini's challenge to create a fashion in a wholly Italian mold, free from the aesthetic shackles of the other side of the Alps.

That soirée for a few select guests in February 1951, at Via dei Serragli 144 A, was a coup de théâtre: the ladies were asked to wear “clothes of purely Italian inspiration”—as the invitation to “Bista” and Nella Giorgini's ball put it—for the occasion of the fashion show staged on the parquet between the couches and, on the second floor of the villa, an exhibition of articles made by the finest craftsmen. The French dominated the scene, but did not have those magic hands for high fashion and all the accessories connected with it, the hats, shoes, bags and a thousand other little secrets of style. “Giorgini took us by the hand and led us into that new world where men and women in colorful clothes rode around on Vespas, clinging on to one another,” wrote the publisher John B. Fairchild, recalling those fabulous days organized by Giorgini, the visionary who succeeded in transforming himself from an agent for American department stores into the prince of Made in Italy, launching the talent of Carosa and Schubert, Emilio Pucci and Roberto Capucci, Irene Galitzine and Fausto Sarli, Simonetta and Jole Veneziani, and then Walter Albini, Missoni, Mariuccia Mandelli Krizia and even Giorgio Armani.

The newspapers of the time spoke of those first shows with amazement and wonder. “Right from the splendid grand staircase, the men-at-arms dressed in 16th-century jacket and breeches, in yellow and red stripes, set the tone for the whole evening,” wrote Mario Bucci in La Nazione. On Tuesday July 12, 1952, when Italy was still yoked to the plow, when with the new hundred lire banknote you could buy four eggs or a liter of Chianti, when Palazzo Vecchio was ringing with the pacifistic and evangelical voice of the mayor Giorgio La Pira, in years in which Great Britain was seeing Elizabeth take her first steps as queen and the United States was carrying out a witch hunt of presumed communist sympathizers. On that day the myth of Italian fashion was born, which perhaps no one has been able to recount with as much passion and poetry as Guido Vergani, joking about that “carbonaro,” i.e. revolutionary, event staged with a good measure of improvisation by the tornado of vitality and ideas that was Giorgini. Epoca entrusted the account of those hot and festive days to a very young reporter of exceptional ability, Oriana Fallaci, who wrote: “In the expectant silence that holds sway only in courtrooms, nunneries, examination halls and fashion shows, the mannequin climbs onto the dais, tripping over her too tight skirt and with her eyes completely hidden by a cloche hat pulled down over her temples …”.

Giorgini had been the first to sense the potential of that new market, in an America with which he had been working for almost thirty years as a buyer: a market that was growing day by day and a society that was changing and attracted to the new. An impression that had infected many of the more enterprising Florentines, the ones who believed that the quality of the Italian style derived in part from the artistic and cultural history of the country, and thus of Florence. An idea rooted in the now fundamental concept of marketing, an intuition that on the surface might seem paradoxical. But a winner: it was a long step from stones to fabrics, from pictures to bags, from palaces to the most fanciful of creations, and yet a very short one for fashion. All it took was to have the right hands and head, as the Gherardini firm showed it had when it started to go with the production of elegant purses for the American market, for those ladies of the affluent middle class of the United States who carried them to cocktail parties and concerts: small and very graceful, with a delicate “G” hidden under the clasp and embroidered or printed in gold, made of velvet, fabric decorated with needlepoint, lace, Renaissance leather or shaded snakeskin.

In those years Italy exported not so many luxury objects and clothes as labor, that of miners, builders and factory workers. But the dream brought its reward, and even more so pure genius, and the will to break through the ceiling of poverty. The Americans were drawn by two things: the price of our products and the good taste of the style and the workmanship. A recipe that was very familiar to the Gherardini family. And so every year the range of samples, of models, of ideas grew. Around the Sala Bianca and its glittering days that projected the allure of Florence into the world, with high fashion but also with the ready-to-wear that was to make a name for itself in the happy eighties. But there were always threats: a group of dissident couturiers in Rome broke away and left Giorgini's “court”; in Milan some young talents chafed at the bit and began to design for emerging brands and manufacturers. It was no accident that in Reggio Emilia there was an entrepreneur-emperor like Achille Maramotti who invented ready-made clothing and gave all the world's women the freedom to dress up in nothing more than an elegant coat.

In Florence, after fifteen years spent pursuing success, things were changing. Responsibility for the calendar of the show passed from Giorgini to Emilio Pucci, Mila Schön made her debut and Krizia appeared on the scene, arriving in the city with a suitcase full of clothes to be presented on the catwalk. Fashion changed because the world had changed: in the space of a few years the young had won themselves a leading role in society that they had never had before. And it was impossible to ignore their world and their desires. In 1969 the celebrated Woodstock Festival marked the watershed of this change. Those naked men and women in loving attitudes broke the rules of dress, and were followed by the wave of jeans, ethnic clothing, the parka and the secondhand. In the meantime the influx that had made fashion more democratic was also spreading. Super exclusive products were no longer necessary. The accessory was the most affordable product and the one most in tune with the new times. In 1975 Pitti Donna was born, with the protagonists of what was to become Italian prêt-à-porter, and in those years Gherardini too appeared on the catwalk with its well-made shirtwaists and leather-trimmed trench coats. Its icon was a little blonde girl who arrived from London. Her name was Twiggy, and her pageboy haircut and ever so modern thinness left their mark on an age. Curves were on the wane and the aesthetic canons of contemporary beauty sprang from this young and androgynous model. At Gherardini they had the courage to hire her for the photos in their catalogs and for their advertising. Once again precursors of the times, following in the footsteps of grandfather Garibaldo.

In those years of boom and prosperity travel was no longer a privilege, who still bought the exclusive sets with the “G” logo that emerged from Via della Vigna Nuova and went all the way to Cinecittà with Mario and Vittorio Cecchi Gori and a celebrity like Marcello Mastroianni, or even the duke and duchess of Windsor. The Gherardini began to come up with new, dynamic and lightweight materials, that were to become the keystone of the label's success at an international level. They also started to design new objects and accessories: they began to think about perfume, to create sunglasses and play around with the prints of headscarves. In short, it was the dawn of the total look.

The Shop Cristina Caldini was taken on as an apprentice by the Gherardini when she was just fifteen years old. Her career, always in the ascendant, lasted until 1995. It was in 1961 that she began work and at that time Ugo and Gino were above all craftsmen and shopkeepers, rather than entrepreneurs. Caldini recounts her memories of those lively and industrious years, and every so often Mauro Biffoli adds his own. While the rich middle class of the province did not hesitate to spend their money, the ladies of the Florentine aristocracy were known for their capricious and often stingy character. Cristina Caldini tells us about Princess C.'s visits to the store. The noblewoman used to bring her two Maremma sheepdogs with her and they would unfailingly cover the floor with mud. The princess would sit on an armchair to look at the models and the dogs stationed themselves next to her, one on each side, like marble statues. The Gherardini showed her all the bags in the store, but she never bought anything on the first visit. After a few hours, in fact, she would make her exit and, addressing the salesgirl, announce on the threshold: “We will be back!”

Mauro Biffoli, for his part, recalls with a smile the time that he looked in from the workshop and saw in the store a distinguished man with one foot placed triumphantly on a stool. Later he came to know that it was Edward, Duke of Windsor, who had come to Gherardini's to purchase a bag for Wallis Simpson. Then as now Gherardini visited for customers in Florence with a rival of great prominence, Gucci, whose store was located just a few meters away, on Via de' Tornabuoni. The two families officially maintained relations of cordial respect and never failed to greet one another and exchange a few words. But Gherardini's workers were warned against even stopping in front of their shop window and this demonstrated the implacable rivalry that, despite appearances, drove the two fashion houses. On the subject of Gucci, Caldini and Biffoli tell of the piece of luck that saved the firm's store from the flood of 1966. It so happened, in fact, that the overflow of the Arno came to a stop right in front of the Loggia Rucellai, filling the Gherardini store with mud and leaving Gucci's unharmed. Cristina Caldini does not forget to tell a detail about the famous shopping bag. The Gherardini had these bags made outside working hours, by long-standing craftsmen of the company and their young assistants. This allowed them to make good money and to build houses in the district that now surrounds the company and that did not even exist at the time.

Softy and Millerighe The revolutionary Softy fabric was created at the end of the sixties as a solution to various drawbacks typical of hides, such as heaviness, a tendency to yellowing and a lack of resistance. Pier Luigi Gherardini decided to find a remedy for these defects, promoting research into the invention of a material capable of ensuring a better quality of product without affecting its aesthetic appearance. Between 1974 and 1975 he commissioned Gommatex Poliuretani SpA to develop a fabric that could meet the brand's requirements. The engineers at Gommatex came up with the idea of coating a piece of 100% cotton material with two colored and adhesive layers of polyurethane. Following application of the film, the material is subjected to roller printing, giving the coated fabric the appearance of kid with the Gherardini logo impressed on it in negative. Out of this came the patent for Ghe Cotone, a type of artificial leather much more elastic and lasting than any other material, with characteristics similar to those of parachute silk. With the technological innovations that took place in the chemical industry in the eighties, the patented material was improved by coating it with three layers of polyurethane. In the same period cotton was replaced by nylon, to make the structure softer and lighter. Between the 1990s and 2005 the product, now called Ghe Softy, evolved further, with a base of 100% polyester instead of nylon and the use of a new generation of polyurethanes that have increased its resistance to light, handling and hydrolysis. Modifications that have turned the fabric into Ghe Softy HHR (High Hydrolysis Resistance). Gherardini Gross or Millerighe was produced in 2000 for the articles in the menswear line, for which a more robust material was needed. Like Softy, it is made by a process of coagulation that binds a textile support, thicker this time, to a film of polyurethane. The embossing of the surface, which creates the ribbed or ribbed piqué effect, is obtained by engraving and pressing the heated material. The result is then coupled on the back with cotton herringbone cloth that is dyed in the required color and printed with the logo of the fashion house. Elastic and malleable, Softy and Gross lend themselves to the printing of varied grounds, such as the kid and textile effects, and their versatility and pleasantness to the touch allow them to be used in the production not only of bags, but also clothing and suitcases.

Energy, creativity, daring and good luck. These were the ingredients of the eighties, the most lively and hectic period in Italian fashion, with the boom in designers and manufacturers who turned themselves into labels and emerged from the soft and protective cocoon of the craft market to take wing in the open skies of luxury and beauty made in Italy. In the “house” of Gherardini, as this was indeed the atmosphere of the firm with its factory at Casellina, not too big and located in the midst of the family's own homes so as not to lose this flavor, everyone worked like crazy to keep up with the orders and to keep the ideas in check. After the flood that devastated Florence along with the store on Via della Vigna Nuova, they struggled to reassemble the fragments of the firm's past, since water and mud had swept away the whole of the archives, the work tools, the manufacturing samples, the precious prototypes, the cardboard and iron models, the rare materials and all the designs. After the water came fire at the store, real bad luck. But the company had to be put back on its feet, a very difficult and painful task on which Pier Luigi and Maria Grazia Gherardini, an inseparable couple, embarked with their daughter Susanna. After finishing her studies Susy, as she was fondly called by her parents, joined the firm and began to take care of the stores, working alongside her father, but then he died while still a relatively young man, in 1980. So the women of the family were left on their own and rolled up their sleeves to defend the authenticity and the value of the brand. Maria Grazia, neie Lunardi, would be in the front line and on the barricades of work for the whole of her life: cheerful, a true Florentine with a clear and proud gaze, she was to become the custodian of the family memories and genius, she whose father had been an artist. Art and craft once again, a recurrent mix in the history of the oldest fashion label in Italy. An enthusiastic experimenter, Maria Grazia personally sifted through the general tendencies that she sensed in the air in Florence and elsewhere in the world and created dynamic and modern products that were a hit in the firm's stores in Milan, Rome, Cortina and Porto Cervo, where the rolls of honor were filled with the dedications and signatures of members of fashionable society, the jet set, the nobility and the wealthy middle class. In the meantime the collections of men and women's wear were shown in Florence, and then came the Milanese catwalks, with models that were always remote from excess and banality. For this was a fashion of ideas and not of pointless fantasies, based on extraordinary intuitions like the use of the revolutionary Softy fabric whose practicality and lightness turned the world of both the bag and the lines of travel accessories on its head. Complete sets, finished in leather, dynamic and vital forms that stemmed in part from the frenetic life of this woman-manager who from Florence set out to roam the world, in love with its beauty and full of interests. All qualities that she infused into the collections, with an eye to the cinema and to literature, to the nature of her gardens and to her love for Duke and Cooky, her beloved and likeable Yorkshire Terriers that were always by her side, at work and by the catwalk.

Accessories were developed at a giddy pace: scarves, umbrellas, what were already designer glasses and the “G” that changed and adapted to the times while preserving its aesthetic force. And then, in November 1982, the master stroke of the Donna di Gherardini perfume, with Women's Wear Daily reporting on it straightaway and talking about an exclusive essence made up of jasmine, lilac, various spices, citrus and jonquil; a scent of Florence that caught on with fans of the brand and with that band of loyal customers who went to the boutique on Via della Vigna Nuova as soon as they arrived in the city, sure that they were always going to find something unique. Like the gold stamps on satin inside the clutch bags, the pleated lace, the handmade clasps: a quality of production that made all the difference, especially in the purses made of python and crocodile skin, a model that had been brought out again because of its continuing popularity and that had been called the foderina or “cover” in 1958. Produced in cardinal red, beige and black, it was the forerunner of the many dress purses that can be seen on catwalks today. In the eighties Gherardini had done all this, almost everything in fact, even giving the bags names, some of them of great charm like the Bellona or the Piattina, made for women of all ages, with that wide range of uses that is the key to modern elegance. Ghe-ghe and Millerighe, more plays on words, a different chic. Not to mention the pocketbooks for men in Florentine leather that called to mind the workmanship of the past and that today are in the hit parade of vintage design. Like the men's shoes and neckties, real collector's items. And then the key cases and beauty cases, the waterproof and sporty bags in deerskin, the billfolds with Centenario metal and even the designer matches. For ten years Maria Grazia held the reins tight and won many races, with Gherardini excelling and becoming all the rage in many markets, above all that of Japan. Then in 1990 she decided to hand those reins over: her daughter Susanna chose to devote herself to painting and sculpture in the studio that faces onto the Boboli Gardens, preferring art to fashion. Today this never-forgotten mistress of fashion would be very happy to know that Gherardini is in the bosom of another great family and the hands of another enterprising woman like Carla Braccialini, surrounded by the affection and dedication of her sons.

The Oggi Collection It was Maria Grazia Lunardi, Pier Luigi's wife, who invented the Oggi Collection at the end of the eighties. She gave the new line this name, “Today” in English, because it was devoted to the kind of modern and dynamic woman of which she felt herself to be a representative. The original logo of the label was designed personally by Lunardi and consisted in the word “Oggi” written in her own hand. The designers created sports-chic models and used practical and resistant materials. Tote, shoulder and bucket bags were made, with a series of innovative combinations and colors. Worthy of note, in fact, are the coupling of cloth and leather, unusual at the time, the borders of natural leather and finally the prints with brightly colored patterns that evoked the brilliant hues of the Venetian mosaic glass of which Maria Grazia is so fond. The collection was taken over in the nineties by the Watanabe holding company, which maintained its casual and youthful inspiration, reaffirmed by the new and more stylized logo that, on a black and white ground, combined the “O” of “Oggi” with the legendary “G” of the fashion house. In fact the Watanabe line was even more eclectic and technological, aimed at a spry and indefatigable woman who was fully in possession of her time, her present, and who lived intensely night and day, an idea symbolized by the black and white of the logo. So in the windows of Gherardini stores appeared bags with geometric shapes, structured with ultra high-tech materials, and bags with softer lines, made out of material woven on a Jacquard loom and printed in black on brown or Shangai Rigato techno-fabric in beige. The comfortable and practical shoulder bags in treated leather, metallic fabrics, velvet and patent leather proved extremely popular. In addition, foreshadowing the eco-style, there were models that gave a nod and a wink to environmentalism, made out of plaited straw and natural fibers. The logo was always present, in the large metal buckles and in the prints, precisely because it was seen not just as a means of advertising, but also as a genuine metaphor of the collection.

And so it was that the Fairy Tale entered the Stock Exchange. With the special sweetness of authentic things, which bloom because they have found the right “home,” one in which they feel welcomed, understood, cared for, treasured and extolled. This is what happened to Gherardini since 2007, when the brand became part of the great and wonderful Braccialini family, from Florence as well, founded on ideas and work, work and ideas. To follow and grow Made in Italy you need a special mindset, a mix of courage and willpower that is not easy to find except in those places and within those people who experience its fascination and strength every day.

Everything goes back to how it was, and even better than before: it is July 2007 when the Braccialini family acquires the company and starts thinking about the brand's international relaunch and the enhancement of the cultural and artistic heritage of this great name in Italian fashion. All the prerequisites are there, along with the hopes. Then Carla Braccialini, as tenacious as Garibaldo and Maria Grazia, knowing everything about this work, especially the imaginative and creative side, like the most jealously guarded secrets of production techniques. And her Braccialini bags have a history almost parallel to that of the iconic “G” brand, at least for the last forty years. Fantasy in power, this could be the trademark of the Braccialini Group, which has recently moved into a futuristic building in the significant industrial area of Scandicci, a workplace that looks like a garden, where time is marked by the light filtering in from everywhere and seeming to really connect you to the sky. A modern and functional architecture where all the bags produced seem to find their ideal refuge, in the design rooms as well as in those where the archive with the most beautiful proposals will soon be rebuilt for each brand. It is thanks to the happiness and wisdom emanating from a place that has taken care of all aspects of environmental impact, down to the orientation according to the age-old principles of feng shui. Spaces designed with future thinking and an enlightened vision that combines the genius loci with the global universe.

Staying in Florence for Gherardini immediately means rediscovering its roots, the strength of its origins that reveal the insights and abilities for a relaunch that starts from the cornerstones of a contemporary and very Italian elegance, perhaps the oldest in the signed accessory sector. The Historical Archive operation begins, first with the mapping of the same, then with an intelligent strategy of recovering the brand's iconic models, those that made it famous among movie stars and jet-set personalities but also among those women who, since the post-war period, have asserted their desire for power and freedom not only through commitment, study, and social redemption but also with a change of image. From poor but beautiful to girls on bicycles, from rebellious protestors to neo-bourgeois climbing hearts and banks, the Italian woman frees herself from all ties and also chooses the freedom of the handbag. Container of dreams but also of everything that...

Re-Thinking Monna Lisa On June 19, 2008, a happening was staged at the Stazione Leopolda in Florence dedicated to the marriage of art and fashion, of past and future: it was entitled “Re-Thinking Monna Lisa Gherardini.” Everything stemmed from Vasari's claim that the woman portrayed in Leonardo's most famous work, the Mona Lisa, could be identified as Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco Bartolomeo del Giocondo and probable ancestress of the founders of the fashion house. In line with the “Archive Project” launched by Braccialini to revive and renew the historic models of the Florentine house, this cultural event focused on a reappraisal of Gherardini's cult Shopping and Bellona bags. In a labyrinthine layout, twelve artists, including Aldo Cibic, Marco Klee Fallani, Fulvia Mendini and the writer Torrick Ablack, put on a live performance of “giocondolatria,” i.e. a reinterpretation of Leonardo's picture, known as La Gioconda in Italian, on panels made of the Softy fabric. These extemporary graffito works were used to make the prints for twelve Shopping bags, renamed Shopping Mona Lisa for the occasion, and thirteen models of the Bellona bag. All the bags were produced in limited editions, and a number of them were auctioned on eBay. These included the Monna Story, a one-off piece hand-painted by the artist Giacomo Piussi, and twelve models of the Monna Rosa, characterized by its rosy tints and inserts in fuchsia crocodile skin. The proceeds from the sale of these one-off models have been used to fund the restoration of a painting in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence. The work is a sacred conversation made up of the Madonna and Child, St. Anthony of Egypt and an as yet unidentified male figure who is giving water to a dog at his feet. The panel was painted in oil by an unknown Florentine artist of the 16th century and comes from a monastery that was abolished a long time ago. The restoration work has entailed a complete cleaning of the picture and the reconstruction of some parts where the paint had come away. In collaboration with the Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio, Gherardini has created a clutch bag made out of a fabric that reproduces a detail of the painting. Its designer, Julie Holyoke, first determined the palette of colors used in the work and then this was utilized as a basis for selection of the yarns of silk. The weaving, carried out by Marta Valdarni, was done on a handloom linked to a computer and took six days. Over 4000 passes of the shuttle and more than 2500 warp threads were required to make a single bag. Only one of them has been produced and it is currently on display in the boutique on Via della Vigna Nuova in Florence: it will be kept in the archives and is not for sale.

And the day came on which the Fairy Tale was listed on the Stock Exchange. With that special gentleness of genuine things, which blossom because they have found the right “home,” the one in which they feel welcome, understood, looked after, mollycoddled and made the most of. This is what has happened to Gherardini since the time, in 2007, when the brand joined the large and happy Braccialini family, Florentine too and also founded on ideas and work, work and ideas. To follow and cultivate the qualities of Made in Italy a special head is needed, a blend of courage and determination not easy to find except in those places and in those people that experience its fascination and force every day. Everything went back to how it was before, and even better than before: it was in July 2007 when the Braccialini family had acquired the company and could start thinking about relaunching the brand at an international level and making the most of the cultural and artistic heritage of this great name in Italian fashion. The conditions were all there, and the hopes too. And then Carla Braccialini is a tenacious person, like Garibaldo and Maria Grazia before her. She knows all about this kind of work, especially the imaginative and creative part, as well as the jealously guarded secrets of the manufacturing process. And her Braccialini bags may not have been around quite so long, but they have a history that runs almost parallel with that of the legendary “G” brand, at least over the last forty years. Power to the imagination: this could be the slogan of the Braccialini Group's factory, which has recently been moved to a futuristic building in the important industrial zone of Scandicci, a workplace that resembles a garden, where the passing of time is marked by the light that enters everywhere and that seems to really put you in touch with the sky. A modern and functional work of architecture where all the bags produced seem to find their ideal refuge, in the design rooms as well as in the ones in which an archive will soon be reconstructed for each brand, with its most beautiful proposals. It must be due to the sense of happiness and wisdom emanated by a place in which care has been taken over every aspect of the environment, including its orientation according to the age-old principles of feng shui. Spaces conceived with an eye to the future in an enlightened vision that marries the genius loci with the universe of globalization.

For Gherardini remaining in Florence has at once meant rediscovering its roots, the force of its origins, which reveal the insights and the capacities of a relaunching that starts out from the cornerstones of a contemporary and exquisitely Italian elegance, as perhaps the oldest of all the firms operating in the sector of the designer accessory. Work has begun on the Historical Archives operation, first with a mapping of those archives and then with an intelligent strategy of revival of the brand's iconic models, the ones that made it famous with movie stars and members of the jet set, but also with those women who since the end of the last war have asserted their desire for power and freedom not just through engagement, study and social emancipation but also a change of image. From the poor but beautiful to the girls on bicycles, from the rebels of the years of student protest to the neo-capitalists who win hearts as well as take over banks, Italian women have shaken off all their shackles and chosen the freedom of the handbag too. Container of dreams, but also of everything that is needed for their dynamic new daily lives. Gherardini's historic models are now ready to take on this latest challenge, just as the market wants to hear again the roar of the Ghe-ghe, to feel the smoothness of the Softy and to relive the chic of the 1212.

Just one year after the takeover the famous Bellona model, launched in 1967 and a striking example of excellence of style and workmanship, was back in the limelight again. In its new life the materials had been enriched (crocodile, gilded leather, embroidery) but it retained its opulent and reassuring form. At Pitti Immagine Uomo 74 in June of that same year, 2008, Gherardini was presented to the world again with a party-event at the Stazione Leopolda, transformed into a temple of pop art. For the maison decided to pay homage in a modern and alternative way to Florence and one of its geniuses: Leonardo da Vinci and his Mona Lisa (whose name was perhaps Lisa Gherardini?). They staged a festival of creativity that brought together painters and graffiti artists, engaged in redesigning the classic Piattina in waxed canvas and pop-style leather handle, decorated with colorful and surprising portraits of the lady with the enigmatic smile, full of energy and expressivity. A way of linking fashion and art again, partly through the donation of a share of the proceeds from the sale of these new models for the restoration of a 16th-century Madonna and Child by an unknown painter in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi. Then would come the 1212 in various formats, some of them more practical and up-to-date than the original, and the designer clutch bag made from the exclusive fabric of the Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio in June 2009. And a multitude of other models that turn around the clasps with the “G” logo, a recognized and esteemed symbol of design. Surprises and yet more surprises, from collection to collection, for a history that is now entering its 125th year, but which is only at the beginning today. With Gherardini expressing its creativity in high craftsmanship, but one that borders on pure art. And with Italian fashion continuing its extraordinary adventure in the realm of beauty and elegance, as always with no equal.